Low Back Pain in the Athlete: Swimmer’s Special

When a swimmer explodes off the starting blocks, each muscle needs to be firing in the proper sequence with full mobility to perform at the top level. Low back pain (LBP) can greatly hinder both performance and mobility. Although not as common as shoulder injuries, studies report low back injuries in 16% of elite swimmers,1 while other studies have reported much higher rates, ranging from 77%-87% in both high load and recreational swimmers.2 Low back pain affects swimmers of all ages, from the novice to elite level. This article will take you through a brief review of the anatomy and function of the back, causes and risk factors for LBP, and finally prevention and management strategies.

Anatomy and Function of the Lumbar Spine

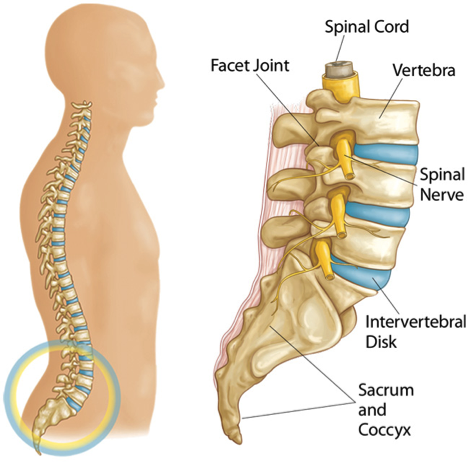

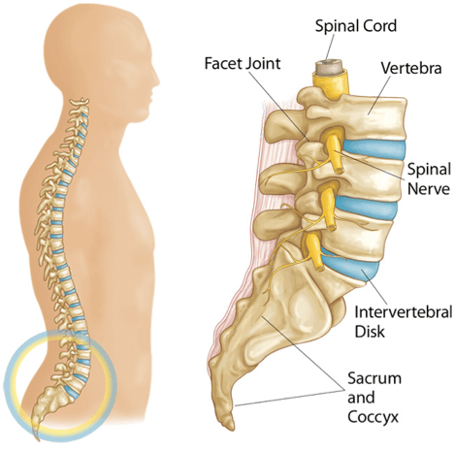

Our spine is composed of a vertebral column (the bones) made up of individual vertebrae separated by soft, flexible intervertebral discs about ½ inch thick, which help absorb the load applied to the spine. In the center of the vertebra is the vertebral canal, which houses the spinal cord (Figure 1). Nerve roots exit through openings in the canal to supply both motor (movement, strength) and sensation throughout the body. The spine is also broken down into four regions: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacrum (Figure 2), with our primary focus today being on the lumbar spine (Figure 2). Shown in the figures, the lumbar spine has a small, natural forward C-shaped curve, which helps dissipate the load on the spine.3

Figure 1 - The Lower Back Explained

Figure 2 - The Spinal Column

The muscles of the spine play an important role in movement, posture, stabilization, and shock absorption. A complex coordination of movements is needed to move the spine, and this is especially important for swimmers. Discussing each specific muscle is out of the scope of this article, but the muscles of the lumbar spine can be broadly categorized by their function: extension, flexion, rotation, and side bending. Extensors bend the spine backwards and keep the spine upright. Flexor muscles, which include the abdominal muscles, bend the spine forwards. If the abs are weak, that natural lordosis of the spine can be exaggerated, leading to excessive loading and low back pain.

Types of Low Back Injuries

Back pain comes in all shapes and sizes with the most common causes summarized below.

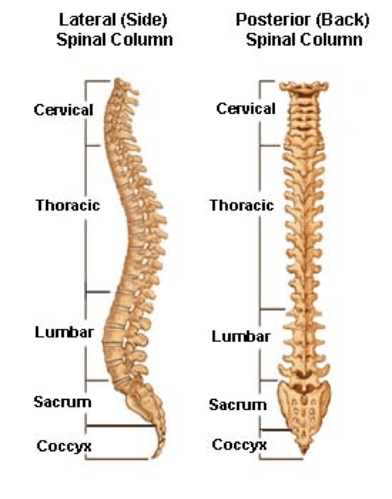

A small crack or stress fracture in the spinal vertebral bones, specifically the pars interarticularis, a small thin portion of bone which connects the upper and lower facet joints (Figure 3), is called Spondylolysis. This type of fracture can occur in sports which involve repetitive stress on the spine, such as swimming, especially in the butterfly and breaststroke. Both of these styles involve excessive loading of the spine, specifically with hyperextension, creating a sheer force on the pars interarticularis. Prevention includes strengthening the trunk during dryland training and focusing on proper stroke technique to avoid hyperextension.

If not managed effectively, that small stress fracture can turn into spondylolisthesis, which is the progression of spondylolysis. In this injury, the fractured pars interarticularis separates, causing the injured vertebra to shift or slip forward on the vertebra directly below it (Figure 3). The treatment changes depending on the degree of bone slippage.

Figure 3 - The Pars Interarticularis and Injuries

Sometimes the cartilage that surrounds the joint can start to break down and be a source of pain. Facet joint arthropathy is arthritis of the facet joints, which link the vertebrae together, located on each side of the bone (Figure 1). Similar to spondylolysis, this typically develops with excessive hyperextension, especially if the pelvis is tilted too far forward, and can be avoided through adequate flexibility of the thoracic and lumbar spine and hip flexors. Strong core muscles (a consistent theme in this article) is a protective factor for excessive loading of the facet joint.

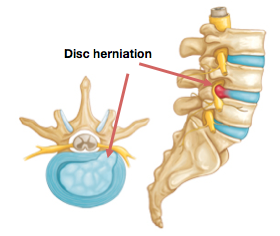

Intervertebral Disc Injuries

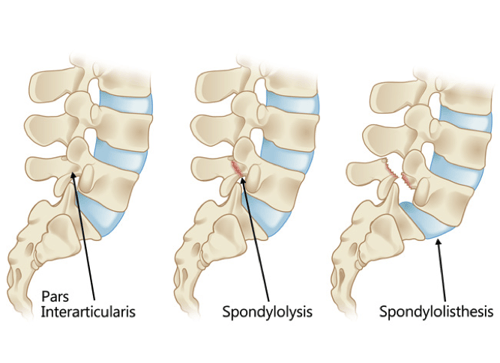

Disc herniations occur when the jelly-like center (nucleus pulposus) of an intervertebral disc pushes against its outer ring (annulus). If the disk is very worn or injured, the nucleus may squeeze all the way through. When the herniated disk bulges out toward the spinal canal, it puts pressure on the sensitive spinal nerves, causing pain in the back and down the leg, referred to as radicular pain (also commonly known as sciatica). In the acute setting, this can be quite painful.

Figure 4 - Herniated Disc in Back

Intervertebral disc degeneration occurs when the disc begins to wear away and shrink, causing the bones to rub against each other, leading to pain and stiffness. Some studies have shown an increased incidence of disc degeneration (defined as either damage to the intervertebral disc, loss of the disc height, and/or displacement or protrusion of the disc outside of the normal contour) in “high-load” swimmers compared to “low-load” swimmers.2 High-load swimmers were defined as competitively swimming for an average of 9 years, with an average swimming distance of 49 km per week, compared to the low-load swimmers, who had been competitively swimming for approximately 5 ½ years, averaging 8.4 km per week. However, in a recent study published in the European Spine Journal, this increased rate was not found, raising the question of whether competitive swimmers are actually at greater risk of intervertebral disc degeneration.4 When swimmers increase the volume and duration of their training, they must remember the increased potential for fatigue and the subsequent breakdown of form, and the need to prioritize core strengthening in their regular dryland routine.Figure 4

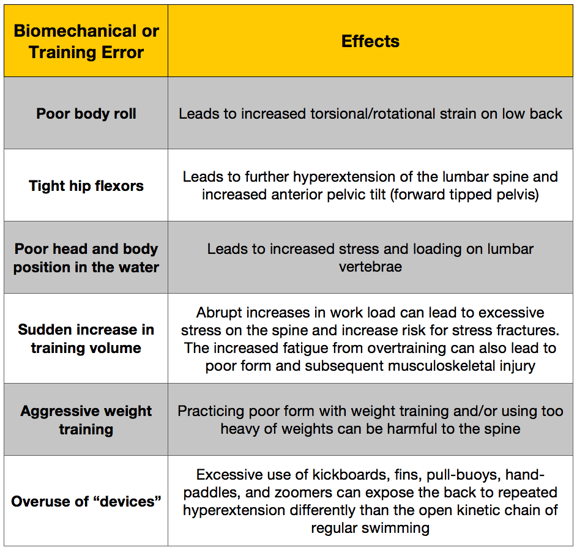

Why Swimmers Get Low Back Pain

In some studies, recreational swimming (i.e., swimming twice a week) can play a protective role in developing low back pain.5 This protective factor is not seen in competitive swimmers. Swimmers take the body into extreme ranges of motion in a repetitive manner and a powerful stroke requires positioning the body in unusual anatomic positions to maximize force production. If a swimmer’s form lacks sound biomechanics, he or she runs the risk of a musculoskeletal injury. For example, additional torsional (rotational) strain is seen when the body does not roll as a whole unit, resulting in abnormal loading at the point in the spine where the rolling stops.6 The low back can also be abnormally stressed if a swimmer demonstrates poor head and body position in the water.

In our discussion of low back pain, the butterfly and breaststroke deserve special attention due to their greater load and stress on the low back. In fact, the irritation seen in the facet joints have historically been referred to as “butterfly back syndrome.”7 The power and range needed in the kick for butterfly and breaststroke is dependent on adequate mobility of the lumbosacral (lower back) joints as well as hip, knee, and ankle flexibility. Specifically, with the butterfly stoke, repetitive flexion and extension of the trunk can, if the pelvis is tilted too far anteriorly (due to tight hip flexors, for example), excessively compress the facet joints in the vertebra. If this compression continues over time, the joint can become inflamed and lead to reflexive back spasms and pain.

Risk factors which have been shown to contribute to low back pain in swimmers are detailed in the table below.6.9

Table 1 - Factors for Lower Back Pain in Swimmers

Prevention and Treatment of Low Back Pain

To avoid a nagging injury like low back pain, swimmers should take a preventative approach. A thorough assessment of mobility of the spine, hips, pelvis, and arms is essential. Correction of muscle imbalances (such as tight hip flexors, weak glutes and core), optimization of pelvic and joint mobility both in static (without movement) and dynamic (with movement) conditions should be addressed prior to ramping up training. Practicing proper form with the guidance of a coach or instructor will not only improve performance but also protect from musculoskeletal injuries including those of the low back. This is especially important in the breaststroke and butterfly, the swimming styles with the greatest incidence of LBP.10 For a swimmer who has a history of lower back pain or troubles, that athlete should be consistent with spinal stabilization exercises, practice sound biomechanics, and avoid sudden increases in training volume.

If a swimmer develops new low back pain, he or she should ideally be evaluated by a physician, especially if it persists and the swimmer is without a history of low back pain. Once a diagnosis has been reached, he or she may need to take a drastic reduction in training and focus on rehabilitation, which will include spinal stabilization exercises (i.e, core stability exercises) to prevent atrophy (or wasting) of the muscles surrounding the spine.11 If a spondylolysis (fracture) occurs, the swimmer may need a longer duration of modified activity (3-6 months) and a lumbar corset for better stabilization.12

Below are some excellent core strengthening and stretching exercises to help prevent low back pain and optimize performance in the water.

Cat-Dog Stretch

Hip Flexor Stretch

Cobra Stretch

SB Streamline Crunches

MB Russian Twists

DB SLDL -2- Press

References

- Goldstein JD, Berger PE, Windler GE et al (1991) Spine injuries in gymnasts and swimmers—an epidemiologic investigation. Am J Sports Med 19(5):463–468.

- Kaneoka K, Shimizu K, Hangai M et al (2007) Lumbar intervertebral disk degeneration in elite competitive swimmers: a case control study. Am J Sports Med 35(8):1341–1345

- Gregory D. Cramer, Chapter 2 - General Characteristics of the Spine, In Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans (Third Edition), Mosby, Saint Louis, 2014, Pages 15-64, ISBN 9780323079549, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-07954-9.00002-5. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323079549000025)

- Folkvardsen S, Magnussen E, Karppinen J, Auvinen J, Larsen R H, Wong C, Bendix T. 2016. Does elite swimming accelerate lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration and increase low back pain? A cross-sectional comparison. European Spine Journal.

- Skoffer B., and Foldspang A.: Physical activity and low-back pain in schoolchildren. Eur Spine J 2008; 17: pp. 373-379.

- Pollard H, Fernandez M (2004) Spinal musculoskeletal injuries associated with swimming: a discussion of technique. Aus Chiropr Osteopat 12(2):72–80

- Cameron JM. Medical problems in competitive and recreational swimming. In: Payne SDW. Medicine Sport and the Law. Blackwell Scientific Publications. 1990. p285-289.

- Becker TJ. Scoliosis in swimmers. Clin Sport Med 1986; 5(1):193- 246. 22.

- Nyska M, Constantini N, Cale´-Benzoor M et al (2000) Spondylolysis as a cause of low back pain in swimmers. Int J Sports Med 21(5):375–379.

- Drori A, Mann G, Constantini N. Low back pain in swimmers: Is the prevalence increasing? Program and Book of Abstracts. Tel Aviv, Israel: The Twelfth International Jerusalem Symposium on Sports Injuries, 1996: 75

- Hides JA, Stokes MJ, Saide M, Jull Ga, Cooper DH. Evidence of lumbar multifidus muscle wasting ipsilateral to symptoms in patients with acute/subacute low back pain. Spine 1994; 19(2):165-72.

- Morita T, Ikata T, Katoh S, Miyake R. Lumbar spondylolysis in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg 1995; 77: 620–625.

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only. Doctors cannot provide a diagnosis or individual treatment advice via e-mail or online. Please consult your physician about your specific health care concerns.

About the Author

Dr. Emily Kraus is a BridgeAthletic performance team contributor where she focuses on topics that are at the forefront of athletics and medicine. She is the incoming Stanford non-operative sports medicine fellow in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Emily has provided medical coverage for events such as the USATF National Track and Field Championships and is the research coordinator for a multi-center study focused on prevention of stress fractures in division I collegiate runners. Emily has finished six marathons, recently ran (and won) her first 50km trail ultramarathon, and placed 56th female in the 2016 Boston Marathon. Emily is passionate about injury prevention, running biomechanics, and the promotion of health and wellness.

Related Posts

What to Consider When Choosing a...

What strength and conditioning coaches should consider when choosing a program design software...

...

2022 NSCA Coaches Conference

The BridgeAthletic team attended the 2022 NSCA Coaches Conference in San Antonio, Texas January 6-8...

2021 Fusion Sport Conference

The BridgeAthletic team attended the 2021 Fusion Sport Summit - North America at the UFC...

.png?width=150&height=50&name=BRIDGEBLOG(1).png)