How Athletes Can Prevent Muscle Cramps | BridgeAthletic

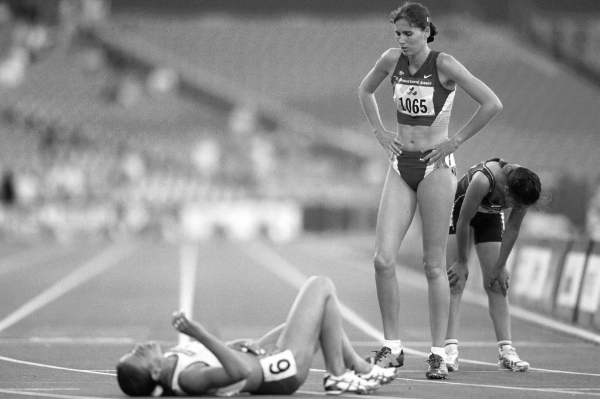

Muscle cramps can be a royal pain in the rear….and hamstring, calf, quad, … the list goes on. Even with the most disciplined training, fueling and hydration plan, a bad cramp can still find a way to hold you down on the day of a competition and completely change your performance. In fact, it is one of the most common medical problems encountered by competitors in an Ironman or any other ultra-distance event as well as affecting athletes of many other sports – especially during the conditioning phases early in pre-season training.

Affected athletes constantly ask why we cramp and how we can prevent it. In this blog, I hope to shed light on what is known and what still needs further study on exercise-associated muscle cramps (EAMC).

Definition

The medical definition of EAMC is a painful, spasmodic, involuntary contraction of skeletal muscle that occurs during or immediately after exercise.1 The non-medical definition is usually far more graphic. My worst muscle cramp experience was during my first 50k at mile 27. Looking back, I would describe it as a seizing, almost-crippling, loss of control of one's own limb(s). I questioned my ability to run another step, let alone finish the race. Not fun, to say the least.

Despite scientists’ and physicians’ abilities to answer some of the most complex medical conundrums, the cause of muscle cramping is still frustratingly elusive.

Salty Solutions

It is well documented that many athletes are “salty sweaters.” Some experts theorize that this lost sodium (via salty sweating) leads to cramping.2 Research on tennis and football players showed crampers lost more salty sweat and had a fall in sodium blood levels compared to non-crampers.3,4 Their recommendation for preventing EAMC is to increase salt intake in the diet and through sports drinks. It should be noted that the level of evidence (i.e., the quality of the study based on well-reviewed standards) is low for these studies and a “one size fits all” approach for management of muscle cramps should be avoided.

Challenging the ‘Lytes Theory

Dr. Martin P. Schwellnus and collaborating researchers have dedicated years to studying EAMC and have discovered it’s not just about the salt.

- Data from several large studies on triathletes show norelationship between dehydration or electrolyte changes in the blood and the development of EAMC.5,6,7

- As muscles tire, there may be an increased risk of EAMC. Early muscle fatigue can occur in hot, humid conditions, increased exercise intensity/duration, or greater depletion of energy stores.7

- Racing at a higher intensity level than training puts one at greater risk of race day EAMC.1

- High intensity training directly before a race (with minimal to no taper) causes muscle injury and "reflex muscle spasms,” leading to EAMC.8

Is it “the nerve”?

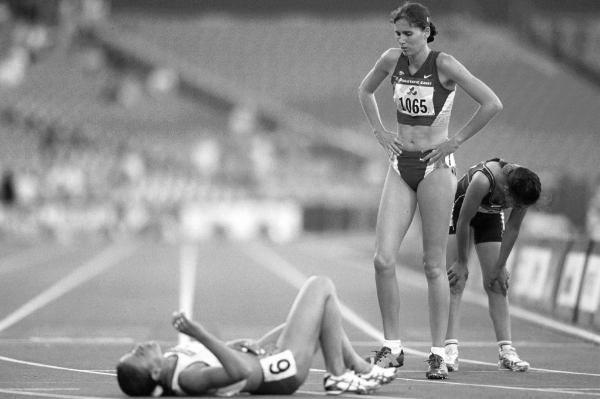

Dr. Rod MacKinnon, who co-founded Flex Pharma, a Boston-based biotechnology company, and Dr. Christoph Westphal out of Harvard Medical School are trying to solve the riddle by not focusing on the muscle, but instead focusing on the nerve. Here’s a breakdown of what they’re studying:

- The theory is that muscle cramps are actually caused by excessively firing nerves, which supply the working muscles.

- The pickle juice and mustard packets some athletes consume to prevent cramps could be triggering special ion channels in the mouth, esophagus and stomach to send calming signals to motor neurons in the spinal cord, which then relaxes the cramping muscle.

- Flex Pharma has calibrated a mixture of ingredients to stimulate these ion channels in the mouth, esophagus, and stomach with the goal of preventing and treating muscle cramps (see schematic below).

- Note: There are still no published large studies demonstrating the effectiveness of this formula.

Figure: FlexPharma

Is there a cure for the common cramp?

With multiple theories about the cause of the cramp, it’s hard to provide a single answer for a cure or prevention strategy. But, if you’ve experienced the debilitating effects of a muscle cramp, you want to avoid a repeat incidence, even if the evidence may be lacking. Based on the research out there, here are some helpful recommendations during training and competition.

Prevention

- Know your training and competition conditions. Factor in humidity, temperature, indoor versus outdoor, altitude and terrain and how this might be different than your usual training conditions.

- If you've cramped in the past, think about all factors that could have played a role (drastic change in intensity, volume, altitude, terrain).

- Focus on form. Muscles most affected by cramping are those repetitively used and confined to a small arc of motion, so focus on form in training to avoid heavy "braking" and try to stretch out the stride with adequate hip and knee flexion and extension.6

- If you’re a “salty sweater,” be sure to increase salt intake in your diet and take in fluids higher in sodium content, especially in the hotter, more humid months. Salt tabs or pills are an easy method, but practice using them in training as some can cause upset stomach.9

- Stay fueled: Athletes should have adequate nutritional intake (particularly carbohydrates) to prevent premature muscle fatigue during exercise.

- Is it “the nerve”? The Flex Pharma research is ongoing, but the theory has a sound scientific basis and, with a little more data, could be a viable option for frequent crampers.

Treatment

- A shot of pickle juice? Some athletic trainers have attributed their success in treating (not preventing) EAMC by using pickle juice, mustard or other high electrolyte beverages. Based on MacKinnon’s studies and a 2010 study on pickle juice10 this may not be due to the electrolyte changes in the blood, but instead by stopping a neural reflex that gets triggered in the esophagus/stomach.

- The evidence: No studies have proven this is effective. If you decide to give it a try, keep the consumption volume low (80mL pickle juice or 2-3 mustard packets) to avoid unwanted stomach upset or lowering your potassium levels (if too low, could lead to abnormal rhythms in your heart).11

- Stretch It Out. If you’re actively cramping, the most effective immediate treatment is to passively stretch the affected muscle.7,

- IV fluids? Treatment with IV fluids is debatable, but in refractory cases, could be used. It is vital to have someone skilled with placing IV’s if you choose this option.8

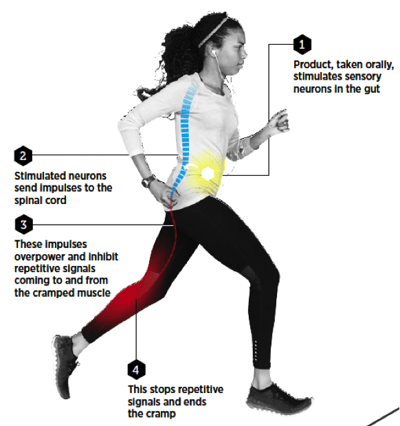

Whether you’re an endurance athlete or just getting in shape for next season, cramps can be a painful detriment to any training regimen or even more so on competition day. Understanding the most common ways to prevent or treat EAMC can change the way frequent crampers get through intense training and competition in challenging environments.

References

- Schwellnus MP. Muscle cramping in the marathon: aetiology and risk factors. Sports Med 2007 ; 37 : 364 – 7.

- Eichner ER. 2014. The salt paradox for athletes. Current sports medicine reports 13 (4): 197-198.

- Bergeron, MF. Heat cramps: fluid and electrolyte challenges during tennis in the heat. J. Sci. Med. Sport 6:18Y27, 2003.

- Stofan, JR, JJ Zachwieja, CA Horswill, et al. Sweat and sodium losses in NCAA football players: a precursor to heat cramps? Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 15:641Y652, 2005.

- Schwellnus MP, Drew N, Collins M. 2011. Increased running speed and previous cramps rather than dehydration or serum sodium changes predict exercise-associated muscle cramping: a prospective cohort study in 210 Ironman triathletes. British journal of sports medicine 45 (8): 650-656.

- Braulick KW, Miller KC, Albrecht JM, et al. Significant and serious dehydration does not affect skeletal muscle cramp threshold frequency. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:710–14.

- Schwellnus MP. Cause of exercise associated muscle cramps (EAMC)—altered neuromuscular control, dehydration or electrolyte depletion? Br J Sports Med 2009 ; 43 : 401 – 8.

- Schwellnus MP, Allie S, Derman W, Collins M. 2011. Increased running speed and pre-race muscle damage as risk factors for exercise-associated muscle cramps in a 56 km ultra-marathon: a prospective cohort study. British journal of sports medicine 45 (14): 1132-1136.

- Eichner ER. 2008. Heat cramps in sports. Current sports medicine reports 7 (4): 178-179.

- Miller KC, Mack GW, Knight KL, Hopkins JT, Draper DO, Fields PJ, Hunter I. 2010. Reflex inhibition of electrically induced muscle cramps in hypohydrated humans. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 42 (5): 953-961.

- Miller KC. 2014. Electrolyte and plasma responses after pickle juice, mustard, and deionized water ingestion in dehydrated humans. Journal of Athletic Training 49 (3): 360-367.

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only. Doctors cannot provide a diagnosis or individual treatment advice via e-mail or online. Please consult your physician about your specific health care concerns.

About the Author

Dr. Emily Kraus is a BridgeAthletic performance team contributor where she focuses on topics that are at the forefront of athletics and medicine. She is the incoming Stanford non-operative sports medicine fellow in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Emily has provided medical coverage for events such as the USATF National Track and Field Championships and is the research coordinator for a multi-center study focused on prevention of stress fractures in division I collegiate runners. Emily has finished six marathons, recently ran (and won) her first 50km trail ultramarathon, and placed 56th female in the 2016 Boston Marathon. Emily is passionate about injury prevention, running biomechanics, and the promotion of health and wellness.

Related Posts

Supplement Safety with Tactical...

Dietary supplements seem like the "magic pill" a tactical operator needs to perform better,...

Eating Healthy on the Go: Tips for Busy...

It's no secret that tactical professionals have weird schedules. So why do health professionals...

Post-Training Nutrition for Tactical...

Eating after a workout can be a challenge for tactical professionals. Having grab-and-go fuel...

.png?width=150&height=50&name=BRIDGEBLOG(1).png)