In the culture of swimming, it’s often expected to “train through the pain” in order to get to the top1. If you consider yourself a competitive swimmer, you likely have experienced shoulder pain at some point in your career, with it being the most common musculoskeletal complaint in swimming with an incidence ranging from 52% to 73% in elite swimmers2. A competitive swimmer usually exceeds 4000 strokes for one shoulder in a single workout3! Needless to say, the shoulder can make or break a swimmer’s season and athletes should focus on prevention to avoid a season-ending injury.

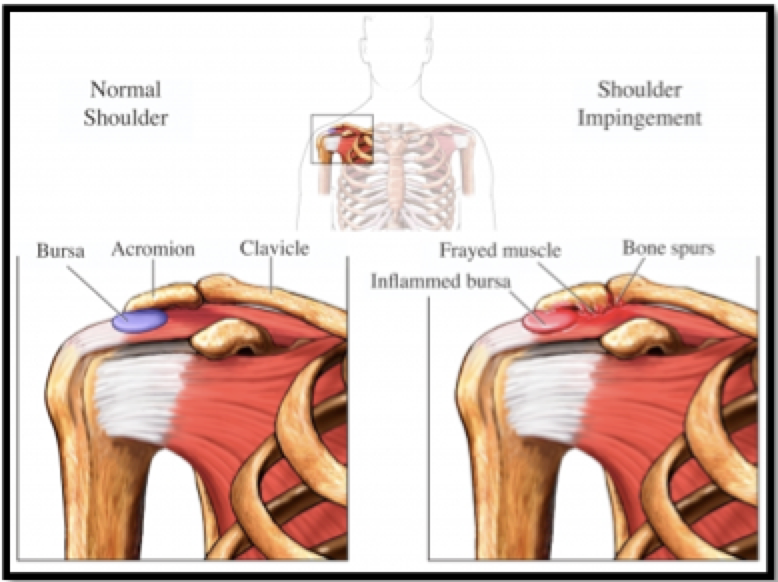

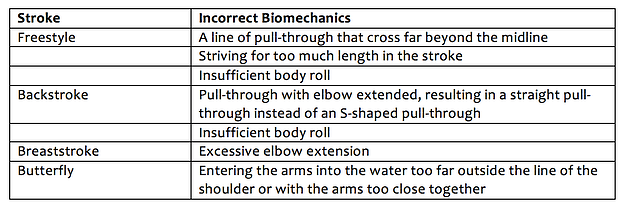

Swimmer’s shoulder usually involves impingement or pinching of the rotator cuff muscles by the acromion bone as they pass through a narrow opening called the subacromial space (see figure below).

Shoulder impingement can be the result of a number of causes, including inflammation of the rotator cuff tendons, increased shoulder joint mobility/laxity and weak muscle stabilizers around the scapula (shoulder blade). Prevention should address swimming form and biomechanics in the water as well as strength training on land.

In the Water: Focus on Form

Competitive swimmers average approximately 18,000 shoulder revolutions per week, mostly from freestyle training4. Regardless of stroke specialty, approximately 80% of practice time is made up of the freestyle. The freestyle stroke is traditionally broken down into 3 distinct phases: hand entry, pull-through, and recovery.

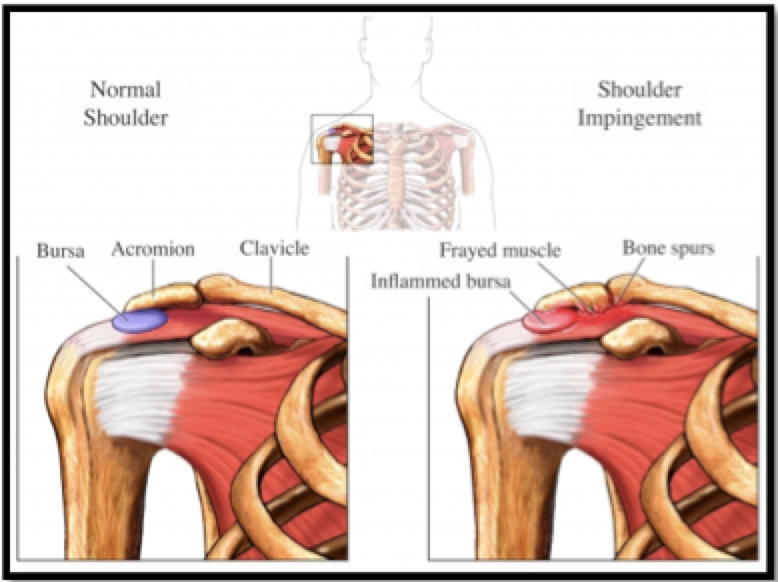

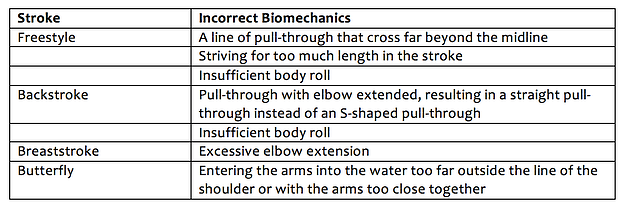

Watch out for the following biomechanical errors during each stroke specialty2:

On Land: Strengthen and Stabilize

Swimmers are subject to shoulder impingement for approximately 25% of their freestyle stroke cycle, even when using proper biomechanics4. For prevention, focus on stretching and strengthening the following: rotator cuff muscles, scapula (shoulder blade) stabilizer muscles, and the core as well as correcting postural imbalances6. Below are some great examples from the athletic trainers at BridgeAthletic. You can also complement your training with yoga and pilates to help with core, balance and flexibility.

Rotator Cuff Exercises: The goal is to strengthen the four rotator cuff muscles of the shoulder. Below is an example of the External Band Rotation. The external rotator muscles of the shoulder are usually weaker than the internal rotators in swimmers.

Shoulder Blade Stabilizing Exercises: Here the focus is to strengthen the muscles in the middle of the upper back and along the sides of the body. These muscles work in coordination with those of the rotator cuff and control the movement of the shoulder blade. Below is an example exercise, the Seated Band Row:

Core Strengthening: This is vital to all aspects of elite athletics, including injury prevention. To read about the importance of core strength and stability for athletes, click here. Below is an example of a core strength and stability exercise, the Quadruped:

If you think you have swimmer’s shoulder or shoulder impingement, seek advice from a sports injury professional who can develop an appropriate rehabilitation program.

References

- Hibberd EE, Myers JB. Practice habits and attitudes and behaviors concerning shoulder pain in high school competitive club swimmers. Clin J Sport Med. 2013 Nov;23(6):450-5.

- Heinlein SA, Cosgarea AJ. Biomechanical Considerations in the Competitive Swimmer's Shoulder. Sports Health. 2010 Nov;2(6):519-25.

- Tovin BJ. Prevention and Treatment of Swimmer's Shoulder. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2006 Nov;1(4):166-75.

- Virag, B., Hibberd, E.E., Oyama, S., Padua, D.A., Myers, J.B.Prevalence of Freestyle Biomechanical Errors in Elite Competitive Swimmers Sports Health. 2014;6(3)

- Bak K. Nontraumatic glenohumeral instability and coracoacromial impingement in swimmers. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1996 Jun; 6(3):132-44.

- Brukner P, Khan K. Clinical sports medicine, 4th ed. Sydney, Australia: McGraw-Hill, 2012:104-105.

For additional injury prevention and training strategies, be sure to check out this post.

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only. Doctors cannot provide a diagnosis or individual treatment advice via e-mail or online. Please consult your physician about your specific health care concerns.

![Bridge Logo Black [1200]](https://blog.bridgeathletic.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Bridge%20Logo%20Black%20%5B1200%5D.png?width=100&height=58&name=Bridge%20Logo%20Black%20%5B1200%5D.png)

.png?width=150&height=50&name=BRIDGEBLOG(1).png)