ACL Injury Prevention

Whether you’re an athlete, coach, athletic trainer, or just an avid sports fan, you likely know someone with an injury to her or his anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or you may have been in the unfortunate situation to experience the injury firsthand. ACL injuries are a common sports-related injury with an annual incidence of 120,000, occurring primarily during the high school and college years.1 Even more shocking is that this rate is increasing, especially in females. This article will focus on ACL injuries in the female athlete (although many recommendations can be applied to both sexes), with discussion on the science behind the injury, the debate on management options, and prevention strategies.

Anatomy: The Anterior Cruciate Ligament

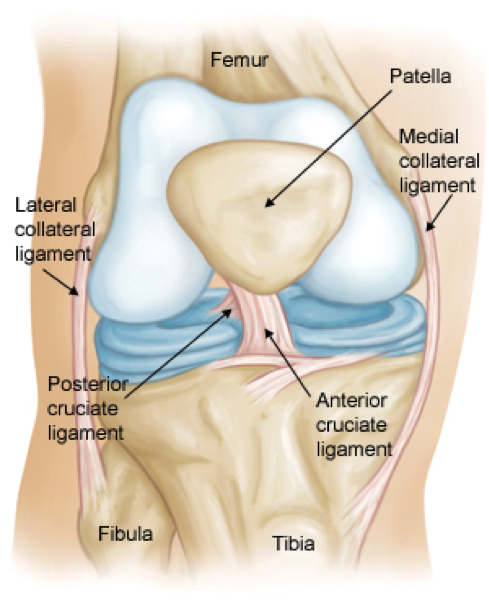

The ACL (Figure 1) is one of the main ligaments to help stabilize the knee by preventing the tibia (shin bone) from sliding forward in relation to the femur (thigh bone). It attaches to the knee at the underside and back of the femur and crosses diagonally through the knee joint to attach at the upper part of the tibia. The posterior cruciate ligament prevents an opposing movement to the ACL and forms an X shape with the ACL. (Fun fact: cruciate is from the Latin word for cross.)

Figure 1: The ACL and associated structures

ACL Injuries: Classification, Symptoms, & Diagnosis

ACL injuries can be divided into two main types: contact and noncontact. A contact injury involves a direct blow to the knee, whereas noncontact injuries are more common and usually involve an “awkward” movement which happens when landing from a jump, rapidly stopping, cutting, or quickly decelerating with change in direction.2

Athletes usually describe pain and a “pop” deep in the knee followed by immediate swelling. Depending on the severity of the tear, they may have some degree of instability or describe a sensation of “giving out” when going downstairs or pivoting. Some degree of stiffness is also quite common. Often, other structures in the knee may also be injured, such as the meniscus or medial collateral ligament (MCL), and the athlete may describe symptoms of locking or clicking in these cases. Diagnosis is made through a good history and physical exam. An x-ray is helpful to ensure there is no associated fracture, while an MRI is helpful to look at injuries to other structures in the knee (i.e., MCL or meniscus) and to aid in surgical planning.

Management of ACL Injuries

Surprisingly, not all athletes who tear their ACL should undergo surgery. There is much debate out of the scope of this article on whether an ACL reconstruction is preferred versus focused rehabilitation alone. Athletes with an isolated ACL injury who are involved in a sport which does not require pivoting, cutting, or rapid deceleration, may be able to return to his or her sport without surgical intervention. In most young athletes who wish to pursue high-level sports with excessive demands on the knee, ACL reconstruction should be pursued, which prompts further decisions on type of graft, recovery, and duration of rehab. These decisions are routinely debated and worthy of a separate discussion in another article.

Why are Females at Greater Risk?

Females are at 3.5 times greater risk of sustaining a non-contact ACL injury and there are a number of theories, with varying degrees of evidence, to explain this alarming statistic:

-Females have a smaller notch for the ACL to attach to the femur and an overall smaller ACL size placing them at greater risk of injury

-A wider pelvis puts greater stress on the ACL

-Greater knee ligamentous laxity (i.e., an increased movement of the ligaments within the joint without any tear) predisposes to injury

Hormonal Differences

Reports have found estrogen receptors on the ACL and theorize that large estrogen influx both at the onset and during puberty may affect the composition of the ACL and its ability to withstand load, although this evidence is conflicting.4

-Research has also suggested females with elevated circulating relaxin levels (the hormone that relaxes ligaments during pregnancy) may be at greater risk of ACL injury.5

-Different Landing Patterns and Neuromuscular Recruitment

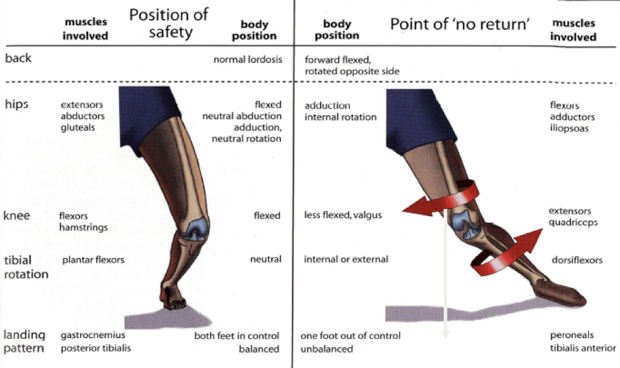

-Females have higher tendency towards risky landing patterns (figure 2):

-More upright/erect position when landing (less knee and hip flexion/bending places a higher degree of stress on the ACL)6

-The femur (thigh-bone) twists internally while the tibia (shin-bone) twists externally, leading to a greater degree of knee valgus (or “knock-knees”)

-Improper balance of power and recruitment pattern (i.e., timing of muscle firing) between the quads and hamstrings

-These factors are especially important because they’re modifiable and can be prevented through proper technique and training

Figure 2 Example of optimal landing pattern (left) versus poor landing pattern (right).

ACL Injury Prevention

With a number of modifiable risk factors identified, ACL injury prevention in female athletes is paramount to ensure a successful, injury-free season. Key components to a comprehensive program include the following:

Balance Training

Studies have tested out balance board regimens and found they did not prevent ACL injury compared to a controlled group (no balance board), suggesting this may not be an effective prevention approach in isolation.7

Landing Patterns and Neuromuscular Adaptation3

A study involving female volleyball, soccer, and basketball players who were assigned a 6-week pre-season program which incorporated supervised exercises working on flexibility, plyometrics, weight training (of the legs, core, and back), and proper landing patterns showed that this type of training can help reduce ACL injuries. These athletes were compared to a female and male control group. Overall the female control group sustained a 3.6 times higher rate of total knee injuries compared with the female intervention group and 4.8 times higher rate of knee injuries compared with the male control group. Take home message: a prevention program incorporating a multi-factorial approach to ACL prevention can be successful in reducing ACL injury rates in female athletes.

Aims of a Successful ACL Prevention Program6

Initiation of program ideally at or prior to onset of puberty to avoid formation of bad habits in the neuromuscular and biomechanical patterns. Even if implemented after puberty, focused ACL prevention is still beneficial and should be incorporated into the sports training.

-Incorporation of neuromuscular training/control, muscle strengthening, plyometrics, education and feedback regarding proper body mechanics and proper landing patterns8

-Timing ideally 6 weeks pre-season, lasting 15-20 minutes (no longer), at least 3x/week. Goal should be to continue throughout the season to help maintain proper form

-Begin and end maneuvers with proper positioning involving knees and hips being sufficiently flexed, jumping/landing with knees over toes, while avoiding knee valgus upon landing, and remembering to “land softly” (landing with more weight on the forefoot)8

-Focus on strengthening hamstrings, but also include gluteus medius strengthening to avoid knee valgus (knock-knees). Any asymmetries in strength should also be addressed8,9

-Plyometrics incorporating high intensity agility drills focused on footwork and quick explosive movements. Start with cutting, jumping, and lateral movements then add in “perturbation” (disturbances) to simulate a real sports situation

Key Takeaways

-Ensure your athletes have a performance training program involving movement patterns commonly performed during training and competition.

-Ideally, implement the program 6-weeks before the season and ensure it highlights proper form. Continue this program throughout the full season.

-Emphasize strength and recruitment of the muscles supporting the knee, with a focus on the hamstrings and glutes to prevent improper loading patterns.

References

- Gornitzky AL, Lott A, Yellin JL, et al. Sport-specific yearly risk and incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears in high school athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2015.

- Boden BP, Griffin LY, Garrett Jr WE. Etiology and prevention of noncontact ACL injury. Phys Sportsmed. 2000;8:53–60.

- Brukner P, Khan K. Clinical sports medicine, 4th ed. Sydney, Australia: McGraw-Hill, 2012:104-105.

- Wild C Y, Steele J R, Munro B J. 2012. Why do girls sustain more anterior cruciate ligament injuries than boys?: a review of the changes in estrogen and musculoskeletal structure and function during puberty. Sports Medicine 42 (9): 733-749.

- Konopka JA, DeBaun MR, Chang W, Dragoo JL. The Intracellular Effect of Relaxin on Female Anterior Cruciate Ligament Cells. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Sep;44(9):2384-92.

- Voskanian N. 2013. ACL Injury prevention in female athletes: review of the literature and practical considerations in implementing an ACL prevention program. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 6 (2): 158-163.

- Caraffa A, Cerulli G, Projetti M, et al. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer. A prospective controlled study of proprioceptive training. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscopy. 1996;4:19–21.

- Renstrom P, Ljungqvist A, Arendt E, et al. Non-contact ACL injuries in female athletes: an International Olympic Committee current concepts statement. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:394–412. Summary of research and recommended guidelines regarding ACL prevention by the International Olympic Committee.

- Myer GD, Chu DA, Brent JL, Hewett TE. Trunk and hip control neuromuscular training for the prevention of knee joint injury. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27:425–48. ix.

- Zahradnik D, Jandacka D, Uchytil J, Farana R, Hamill J. 2015. Lower extremity mechanics during landing after a volleyball block as a risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament injury. Physical Therapy in Sport 16 (1): 53-58.

- Zahradnik D, Uchytil J, Farana R, Jandacka D. 2014. Ground Reaction Force and Valgus Knee Loading during Landing after a Block in Female Volleyball Players. Journal of human kinetics 40 : 67-75.

- Favre J, Clancy C, Dowling AV, Andriacchi TP. Modification of Knee Flexion Angle Has Patient-Specific Effects on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk Factors During Jump Landing. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Jun;44(6):1540-6.

- Figure 2 Image from Brukner P, Khan K. Clinical sports medicine, 4th ed. Sydney, Australia: McGraw-Hill, 2012:104-105.

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only. Doctors cannot provide a diagnosis or individual treatment advice via e-mail or online. Please consult your physician about your specific health care concerns.

About the Author

Dr. Emily Kraus is a BridgeAthletic performance team contributor where she focuses on topics that are at the forefront of athletics and medicine. She is the incoming Stanford non-operative sports medicine fellow in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Emily has provided medical coverage for events such as the USATF National Track and Field Championships and is the research coordinator for a multi-center study focused on prevention of stress fractures in division I collegiate runners. Emily has finished six marathons, recently ran (and won) her first 50km trail ultramarathon, and placed 56th female in the 2016 Boston Marathon. Emily is passionate about injury prevention, running biomechanics, and the promotion of health and wellness.

Related Posts

The Formula for Individualized Training

With over 18 years of experience coaching youth, high school, collegiate, Olympic, and...

Beach Volleyball: 3 R’s to Keep Up With...

At this point in the season you are in full swing of your beach season. In our previous...

Increase Agility, Power, and Speed...

A large factor in achieving success in volleyball is the ability to quickly react to situations on...