Leaning into a Bottom-Up Framework in Tactical Human Performance Optimization

All views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policies or opinions of the United States Government, The Department of Defense, or The Department of the Air Force.

The process of determining the optimal selection of exercises, targeting specific anatomical structures, implementing progressions and regressions, and emphasizing goals within a strength and conditioning (S&C) or "human performance optimization" (HPO) program is a subject of ongoing discussion among professional coaches, administrators, and other key figures in the realm of sports performance.

Unlike traditional academic, club, collegiate, and professional sport settings, the "tactical" environment commonly includes various confounding variables, including work schedules, family responsibilities, career obligations, and more. Instead of the usual academic or athletic focus, these daily responsibilities are prevalent and often come with increased urgency for military, police, and fire professionals.

Leaders and administrators responsible for the mission-effectiveness and budget-compliance of these Tactical Professional Organizations have recently begun employing S&C professionals to supplement the readiness and performance of their unit or organization. As it happens, introducing these resources also leads to decreased expenditures related to insurance and healthcare – when utilized. HPO professionals must align delivery parameters and methods with unit goals and standards to create a program that satisfies both the organization and end-users. Stakeholder conversations at all levels provide insight into necessary and possible adjustments within the unit's operating structure.

This sequence of events has paved the way for a more structured approach within our organization, focusing on elevating READINESS as our foremost priority, followed by enhancing individual and unit PERFORMANCE through physical fitness testing and key job-task assessments. As an HPO team, our third objective is to elevate individual capabilities beyond readiness, cultivating a level of RESISTANCE to known stressors and bolstering operational stamina.

Our main focus when designing the parameters of our program was to create a robust method that allows for flexibility in selecting exercises to match individual and team equipment availability, strength levels, and readiness, while also considering the diverse range of movement skills and capacities. Rather than prescribing a one-size-fits-all approach, our program serves as a bridge between our professional expertise and the specific contextual needs of those we support.

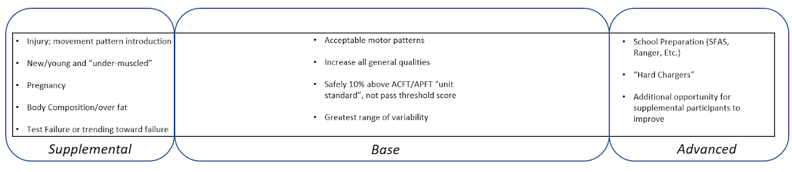

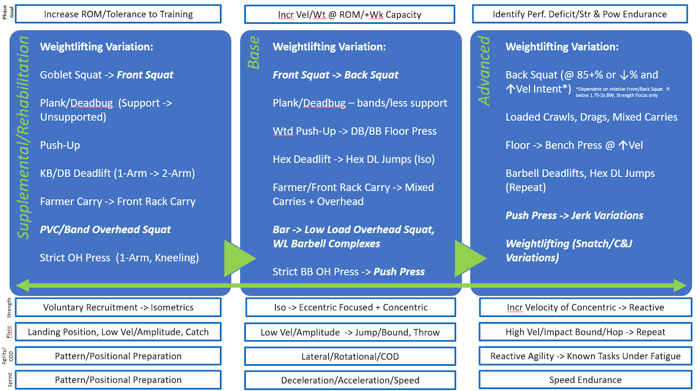

Given the diverse needs of our Tactical Professionals, our program must cater to individuals recovering from serious injuries or surgeries, as well as those gearing up for Special Forces Assessment and Selection (SFAS) [Figure 1]. With a high ratio of trainees to coaches, our program structure offers ample flexibility in daily, weekly, and monthly execution. I will delve into the meticulous selection of movements and goals we employ to shape our resistance training approach. While speed, agility, change of direction, and energy system development are integral components of our program, delving into them further would require a more in-depth discussion.

Figure 1: Supplemental, Base, and Advanced Program Segments

Segmentation of the Program

As stated, the primary staff mission is maintaining the highest number of people available daily to do their job. Which includes being ready to deploy, fight, and win. Whatever their specialty, any individual not ready to perform leaves a greater burden on those around them. It may not be a huge surprise, but there is a large time-demand on our average trainee. We try to do our part to reduce that load on the individual by providing programs, education, and support geared to deliver the most impact in the least amount of time.

Supplemental

Although the Supplemental Segment may not be the largest component of our program in terms of physical participation, it plays a crucial role as the driving force behind our measurable impact. This segment serves as the primary avenue for "Return to Duty" and introductory training, catering to individuals recovering from injuries or illnesses, returning from pregnancy, or facing challenges related to body composition or fitness test scores. Figure 2 (below) outlines the exercises that form the foundation of our progressive movement sequences, along with the goals of the introductory or rehabilitation phase. Emphasizing a "bottom-up" approach, we aim to meet individuals where they are, providing flexibility to tailor the program to their specific needs and abilities.

We systematically introduce positions, load, and velocity across growingly more complicated patterns to provide adequate stimulus for improvement, a basis for understanding the training process, and greater overall movement competency at increasing workloads. General adaptation is our bread and butter which means we can be especially flexible with movements used during the introductory period. Movement flexibility as a principle also provides greater tolerance to train around injury and aid in overall health and healing for those with injury-related duty and/or physical activity limitations. This segment of the program has included up to 10-15% of the total participation base depending on unit type, total training-age of the unit, and other variations. Anecdotally, similar programs have seen reductions up to 50-60% in more chronic musculoskeletal injury rates over time, which leads to a greater participation in the Base Segment and increased readiness numbers for the unit.

Base

The majority of our program operates without direct oversight from coaching staff. In order to accommodate time constraints, a large operational population, military customs, and conflicting daily responsibilities, Non-Commissioned and Commissioned Officers take charge of guiding and monitoring physical training, with support from other skilled and enthusiastic personnel. Our deliberate choice to focus on exercises with lower technical demands while still addressing essential motor capacities ensures a balanced approach. For individuals interested in more demanding exercises like power cleans or snatches, we progress them through unloaded barbell complexes until supervision is available. This method minimizes the risk of injury from improper loading, promotes volume with sound movement patterns, and reflects the emphasis on foundational conditioning programs commonly seen in the military community.

The Base Segment encompasses the majority of the unit, roughly 85-90% at any given time, including those soldiers classified as Advanced, which will be elaborated on later. The primary objectives of the Base programs are to uphold baseline readiness by reducing injuries and addressing body composition, ensure unit members pass all fitness tests with ease, and seamlessly integrate with existing occupational training schedules to manage accumulated stress levels. Effective communication between the HPO team and unit planners is crucial to align training loads with immediate goals. For instance, pre-deployment training calendars are typically packed with time-sensitive tasks, and coordinating schedules to ensure soldiers receive optimal training at critical times is a collaborative effort within the team.

Advanced

In coordination with the Base programming, soldiers who are seeking to enhance their performance to an even higher degree attend additional training sessions designed to identify and improve their individual performance deficit and/or prepare them of the known tasks to be encountered during a selection process, e.g. SFAS, Ranger School, etc. Coordinating training, nutrition, stress-management, across both the Base and Advanced program requires daily communication and coordination between the HPO Team and the individual.

This is also where more “traditional” weightlifting variations may occur. Often, soldiers at this point in their development have demonstrated the tissue integrity and compliance, motor coordination across multiple joints, and maturity required to utilize movements which challenge their force, velocity, and coordinative abilities at the same time. Though still context and individually dependent, introducing power- and hang-variations of the lifts at loads which more closely resembles true “weightlifting” training does occur during this phase. Full weightlifting movements may be included, but rarely at maximum effort.

Figure 2: Program Segment Overview and Phase Goals

Figure 2: Program Segment Overview and Phase Goals

Exercise selection and variety serve as valuable tools in this program segment. The Front Squat serves as the lower body strength movement that underpins the Base programs and utilizing more Back Squats in the Advanced program provides a more concentrated loading stimulus to the body, which means we can reduce volume necessary to drive adaptation, as well as a slightly different loading position to avoid excessive wear and tear associated with repeated movements across a training week.

The squat example is just one component of our movement variety as a modifiable variable. Safely modifying motor patterns can arguably be identified as the greatest instrument use to reduce overuse behind volume itself, especially within our program and working with soldiers who are already under a high-volume workload demand which cannot always be reduced to “acceptable” levels.

Summary

Movement skill enhancement and power development is a bottom-up process, meaning the process starts where the trainee is capable and not where you think they should be. By layering developmental goals with contextual realities, overlayed onto a functioning skeleton of measurable progress markers, a living and breathing system of improvement can be implemented into the dynamic environments common to the U.S. military, Law Enforcement, and Fire organizations. Olympic weightlifting is a wonderful tool to include into any program if power, coordination, and strength are desired, but the movements themselves are simply tools – not the only way.

Willingness to abandon pre-conceived notions of someone SHOULD be doing and placing them into a situation that challenges them just on the brink of what they CAN do will likely lead to higher quality results with the least amount of work necessary. Having a thoughtfully constructed framework of exercises and progressions based in valid methods that are well-understood by the HPO practitioner can also reduce decision fatigue and preserve time and energy for what actually matters; actively engaging with those you serve.

About the Author

JD Mata is a 10-year United States Air Force veteran with multiple deployments supporting Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom, as well as Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa. Following his honorable discharge in 2014, he has been involved in Strength & Conditioning as a coach and researcher in the military, law-enforcement, college, pro, and Olympic human performance communities which has resulted in multiple peer-reviewed scientific journal articles. Over that time, JD has amassed 19 years of experience in the general and specific development of tactical and athletic skills that contribute to success and survivability in competition and in life. Now pursuing his PhD, JD spends his free time exploring nature with his dog Lex, playing recreational sports, training for the sport of Olympic weightlifting, and enjoying watching his three beautiful nieces growing into strong, confident young women.

Related Posts

Six Benefits of Exercise on Mental...

Exercise is not only vital for physical health but also plays a transformative role in mental...

4 Easy Steps to Launch and Sell a...

The holiday season offers a unique opportunity for personal trainers to reach more clients and...

4 Proven Offers to Attract Clients and...

Standing out in the competitive world of personal training and fitness coaching requires more than...

![Blog CTA Med.[button] - tactical - optimize](https://blog.bridgeathletic.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Blog%20CTA%20Med.%5Bbutton%5D%20-%20tactical%20-%20optimize.png?width=1240&height=570&name=Blog%20CTA%20Med.%5Bbutton%5D%20-%20tactical%20-%20optimize.png)