Sports Specialization: Striking the balance between performance and injury prevention

Ask active young athletes who they look up to and good chance you’ll get the name of an Olympian, professional athlete, or perhaps the next rising star in their sport. Many aspire to achieve elite status, or a future collegiate or professional career in a specific sport. This can lead to an excessive amount of pressure by the athlete, coaches, parents, and teammates to pick a sport to specialize in early and put in hours of training year-round. Is this the only way to achieve the skill and experience to make it to the top? What are the downsides of this? This sports science article will provide some background on sports specialization, discuss the risks of early sports specialization, how early versus late influences performance, and, finally, provide some recommendations to coaches, athletes, and parents on training.

Background and Definitions

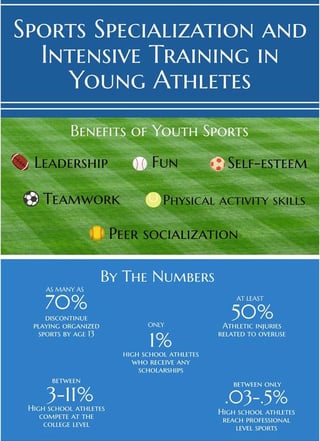

Whatever happened to the neighborhood pick-up game? Does it still exist? What about the multi sport high school athlete? Youth sports has changed dramatically over the years, with greater emphasis on organized sports. Some select or travel leagues start as young as seven years of age. An estimated 60 million youth aged 6-18 years old participated in organized sports, an increase from 45 million in 1997.1 Figure 1 outlines benefits of organized sports and some surprising statistics on the high dropout rates and incidence of overuse injuries.

Figure 1: The Benefits of Sports Specialization in Young Athletes

Obtained from Brenner’s Sports Specialization and Intensive Training in Young Athletes2

Sports specialization is defined as intensive year-round training in a single sport at the exclusion of other sports.3 The degree of sports specialization can be defined as low, moderate, or high depending on whether the athlete 1) chooses a main sport, 2) participates for greater than eight months per year in one main sport, and/or 3) quits all other sports to focus on one sport.4

A theory proposed by Côté and colleagues called the Developmental Model of Sport Participation (DMSP) introduces two distinct types of early sport environments that can potentially lead to elite performance in sport: early sampling or early specialization.5 Early specialization is characterized as a high volume of deliberate practice with a low amount of deliberate play in a single sport with a focus on performance as early as age six or seven whereas early sampling (or diversification) is defined as involvement in various sports with a focus on deliberate play.6 To clarify further, deliberate practice is highly structured activity with the explicit goal to improve performance while deliberate play is intentional and voluntary nature of informal sport games designed to maximize inherent enjoyment. The ongoing debate is whether early specialization will eventually lead to elite sports performance or, instead, injury or burnout.

Early Sports Specialization and Performance

A commonly cited example of early sport specialization is top professional golfer, Tiger Woods, who was introduced to golf at the ripe age of two years old. Many parents believe sport specialization is the only way to gain the competitive edge and achieve success in sport. In contrast to the previously described deliberate play, deliberate practice is the approach used in sports specialization, which often uses a training regimen that is usually not in accordance with the child’s motivation to participate in sports.6,15

What about the “10,000 Hours” Rule? The media has often misquoted Ericcson’s “10,000 Hours” study with the misconception that in order to succeed, an athlete needs to have 10,000 hours of practice/competition to truly find mastery in that field. In fact, the research was based on studies of small numbers of chess champions and highly selected elite musicians whose success was attributed to very high volumes of training. With the exception of a few sports, such as gymnastics and figure skating, the odds of excelling to the elite level in sports do not appear to be increased by early sports specialization.4

In contrast, Wayne Gretzky, arguably the greatest hockey player of all-time, played baseball and lacrosse in his youth. A study of NCAA Division I athletes found that 70% did not specialize in their sport until at least age 12 and 88% had participated in more than one sport.17 In addition, athletes who engaged in sport-specific training at a young age had shorter athletic careers.6

Instead of early specialization, emphasis should be placed on early diversification, which allows the athlete to explore a variety of sports while growing physically, cognitively, and socially in a positive environment and developing intrinsic motivation.2 Current evidence suggests that delaying sport specialization for the majority of sports until after puberty (late adolescence, ∼15 or 16 years of age) will minimize the risks and lead to a higher likelihood of athletic success.2

Early Sports Specialization and Overuse Injury

Numerous studies have examined the rates of injury in early sports specialization:

-

Studies by Jayanthi and Hall examined the rates of overuse injuries in children following early sports specialization and found that sports specialization was significantly associated with the onset of all injuries, including serious overuse injuries8 and knee injuries.

-

That same study by Jayanthi et al. found that athletes who participated in organized sports compared with free play time in a ratio of greater than 2:1 had an increased risk of an overuse injury. Additionally, young athletes who participated in more hours of organized sports per week than their age in years also had an increased risk of an overuse injury.10

-

A study on 2721 high school athletes found that increased overall sports exposure was the most important risk factor for injury, especially once training volume exceeded 16 hours per week. 7 Degree of sports specialization in this study was not accounted for.

Why increased risk?

Several theories exist for why the increased injury risk:4

-

Year-round exposure to a single sport. A study on youth baseball pitchers found greater risk for shoulder and elbow surgery in those who pitched greater than eight months per year.11

-

Repetitive technical skills and high-risk mechanics. Certain sports, such as tennis and baseball, carry a greater risk of overuse injuries due to the repetitive nature of certain movements. For example, an early introduction of the kick serve in tennis or higher pitching volume and poor pitching mechanics led to increased injuries to shoulder and elbow.12,13

-

Overscheduling and competition. Studies show injury risk is higher in competition, especially intense competitions lasting 6 hours or longer.14

-

Psychological burnout: Burnout in athletics is a topic that deserves its own dedicated article, but burnout from early sports specialization likely results from a combination of physical and psychological factors. Less input into training and sport-related decisions, lack of “fun” at earlier ages, and heightened performance pressure at older ages.

Recommendations:

-

Participating in multiple sports, at least until puberty, decreases the chances of injuries, stress, and burnout in young athletes.2

-

Having at least a total of 3 months off throughout the year, in increments of one month, from their particular sport of interest will allow for athletes’ physical and psychological recovery. (Young athletes can still remain active in other activities to meet physical activity guidelines during the time off.)2

-

Young athletes having at least one to two days off per week from their particular sport of interest can decrease the chance for injuries.

-

Weekly hours of sports participation should not exceed the child’s age (in years) with a recommended maximum of 16 hours per week.4

-

Other age-related play such as pitch counts in baseball should be followed to avoid excessive repetitive movements.15

-

Youth who specialize in a single sport should plan periods of isolated and focused integrative neuromuscular training to enhance diverse motor skill development and reduce injury risk factors.4

References

- National Council of Youth Sports. Report on Trends and Participation in Organized Youth Sports. Available at: www. ncys. org/ pdfs/ 2008/ 2008- ncysmarket-research- report. pdf. Accessed December 15, 2015.

- Brenner, COUNCIL ON SPORTS MEDICINE AND FITNESS. Sports Specialization and Intensive Training in Young Athletes. Pediatrics Sep 2016, 138 (3) e20162148; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-2148.

- Jayanthi N, Pinkham C, Dugas L, Patrick B, LaBella C. Sports specialization in young athletes: evidence-based recommendations. Sports Health. 2013;5:251-257.

- Myer G D, Jayanthi N, Difiori J P, Faigenbaum A D, Kiefer A W, Logerstedt D, Micheli L J. 2015. Sport Specialization, Part I: Does Early Sports Specialization Increase Negative Outcomes and Reduce the Opportunity for Success in Young Athletes?. Sports health 7 (5): 437-442.

- Côté, J., & Fraser-Thomas, J. (2007). Youth involvement in sport. In P. Crocker (Ed.), Sport psychology: A Canadian perspective (pp. 270-298). Toronto: Pearson.

- Côté J, Lidor R, Hackfort D. ISSP position stand: to sample or to specialize? Seven postulates about youth sport activities that lead to continued participation and elite performance. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;7:7-17.

- Rose MS, Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. Sociodemographic predictors of sport injury in adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(3):444-450.

- Jayanthi N, Dechert A, Durazo R. Training and specialization risks in junior elite tennis players. J Med Sci Tennis. 2011;16:14–20.

- Hall R, Barber Foss K, Hewett TE, et al. Sport specialization’s association with an increased risk of developing anterior knee pain in adolescent female athletes. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24:31–35.

- Jayanthi NA, LaBella CR, Fischer D, et al. Sports-specialized intensive training and the risk of injury in young athletes: a clinical case control study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:794–801.

- Olsen SJ, Fleisig GS, Dun S, Loftice J, Andrews JR. Risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:905-912.

- Kovacs M, Ellenbecker T. An 8-stage model for evaluating the tennis serve implications for performance enhancement and injury prevention. Sports Health. 2011;3:504-513.

- Fleisig GS, Weber A, Hassell N, Andrews JR. Prevention of elbow injuries in youth baseball pitchers. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2009;8:250-254.

- Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train. 2007;42:311-319.

- Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Waterbor JW, et al. Longitudinal study of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1803-1810.

- Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Römer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100(3):363–406.

- Quitiquit C, DiFiori JP, Baker R, Gray A. Comparing sport participation history between NCAA student-athletes and undergraduate students. Clin J Sport Med. 2014;24(2).

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only. Doctors cannot provide a diagnosis or individual treatment advice via e-mail or online. Please consult your physician about your specific health care concerns.

About the Author

Dr. Emily Kraus is a BridgeAthletic performance team contributor where she focuses on topics that are at the forefront of athletics and medicine. She is the incoming Stanford non-operative sports medicine fellow in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Emily has provided medical coverage for events such as the USATF National Track and Field Championships and is the research coordinator for a multi-center study focused on prevention of stress fractures in division I collegiate runners. Emily has finished six marathons, recently ran (and won) her first 50km trail ultramarathon, and placed 56th female in the 2016 Boston Marathon. Emily is passionate about injury prevention, running biomechanics, and the promotion of health and wellness.

Related Posts

The Best Bench Press Variation You’re...

This post is part of our Coaches Corner series with Taylor Rimmer. Taylor is NSCA-CPT, StrongFirst...

Does Powerlifting Harm Heart Health?

A recent study has discovered that a 12-week supervised strength training program (SSTP) may result...

-1.png)

Barefoot Running: Is It For You? |...

Run Free: Consider Less Cushion

Updated October 2020:

With more athletes looking for ways to...