How to Beat the Heat in Training and Competition: Part 2 - Hydration

Part II: Hydration

The month of August brings the commencement of major international competitions and Fall sports practices. August also brings with it some of the hottest and most humid days of the year, which makes for a well-timed continuation of the discussion on how to optimize performance when training and competing in the heat. Part one focused on the benefits of heat acclimatization on thermoregulation for optimal performance, but proper hydration can truly make or break an athlete come game day. In this article, I will discuss why hydration is so important and then provide simple hydration strategies before, during, and after exercise.

Practice Makes Perfect

During competition athletes can easily become distracted by the excitement and intensity of the moment and run the risk of improper hydration and potential underperformance. To prevent this avoidable misstep, athletes should always use training as a way to practice different hydration strategies.

When we exercise in the heat, our blood vessels dilate, our sweat rate increases and we become dehydrated unless we replace our fluid losses.1 Further, our dehydrated state leads to less blood getting pumped back to the heart and difficulty with blood pressure regulation.2 As a result, our capacity to tolerate exercise is reduced and our heart is working harder to exert the same amount of effort in a more hydrated state. Clearly, this is not an ideal scenario.

Despite these physiologic effects, there is an ongoing debate regarding whether dehydration is that detrimental to sport performance. Although many studies are consistent with the theory of performance impairment, some recent studies on cyclists did not show an effect on cycling performance.3,4,5 It should be noted these cyclists were highly trained and competing in ambient conditions. Thus, in conditions where severe dehydration is expected, proper fluid replacement is essential.

Pre-Exercise

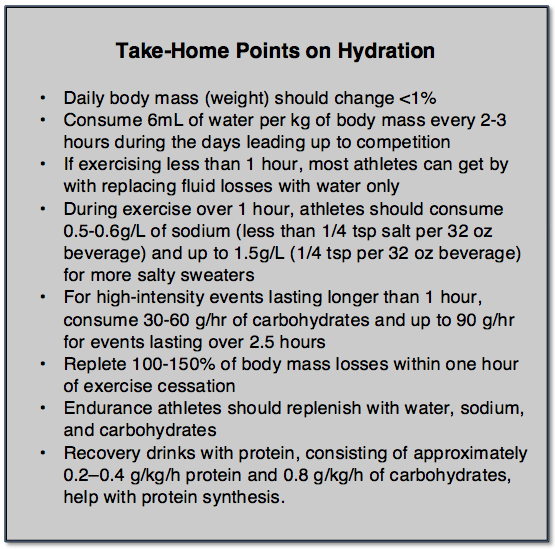

Leading up to training and competition, athletes should maintain a state of “euvolemia” (balanced volume of total body water). They should consume 6mL of water per kg of body mass every 2-3 hours during the days leading up to competition, including 2-3 hours before training.1 To evaluate proper hydration, daily body mass should change <1%. To accurately measure daily body mass, the athlete should be weighed first thing in the morning, after completely emptying the bladder and drinking approximately 1-2 liters of fluid the evening prior. 6

During Exercise

Sweat rate is highly variable between athletes, with some athletes losing up to 2.5 liters per hour (that’s more than a large soda bottle) and others lose more electrolytes (the salty sweater).7,8,9 With proper heat acclimatization, sweat rate will increase, but the concentration of electrolytes in the sweat will be less (i.e., less salty sweat). Even with these heat adaptations, fluid and electrolyte replacement is needed. Salty sweaters, usually easily identified by having a nice residue of salt on their body and clothes after exercise, need additional supplementation during, and sometimes before, exercise. During exercise over one hour, athletes should consume 0.5-0.6g/L of sodium (less than 1/4 tsp salt per 32 oz beverage) and up to 1.5g/L (1/4 tsp per 32 oz beverage) if athletes suffer from muscle cramping (more on the muscle cramping debate here).10,11 High-intensity events lasting longer than one hour warrant the addition of carbohydrates. Athletes should consume 30-60 g/hr of carbohydrates and up to 90 g/hr for events lasting over 2.5 hours.12

If exercising less than one hour, most athletes can get by with replacing fluid losses with water only. High amounts of pure water intake without electrolyte replacement can dilute blood sodium levels and raise the risk of exercise-associated hyponatremia (rapid drop in sodium levels in the blood), which can have serious, devastating consequences.11 The longer endurance events yield the greatest risk.

Drink to Thirst?

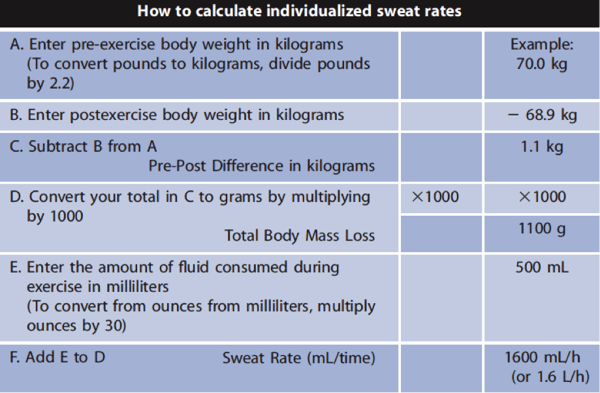

The concept of “drinking to thirst” has stirred up debate as of late as some athletes don’t have readily available fluids throughout exercise or competition, running the risk of under hydrating in warmer climates or over hydrating in cooler climates.13 Instead, athletes should be made aware of their sweat rates to main an optimal balance of “euhydration” or “euvolemia.” Therefore, exercising individuals should be made aware of their sweat rates so that they are neither in a state of hyperhydration nor lose so much fluid that it begins to impair their performance or physiological responses to exercise.14 Table 1 breaks down how to calculate sweat rates.

Table 1

Lopez, R. Exercise and Hydration: Individualizing Fluid Replacement Guidelines Strength & Conditioning Journal. 34(4):49-54, August 2012.

After Exercise

Once the buzzer goes off, you cross the finish line or you complete that hard workout, it’s time for a smart recovery. To optimize and expedite the recovery process, athletes need to rehydrate and replenish lost stores, with a goal of repleting 100-150% of body mass losses within one hour of exercise cessation (side note: repleting 150% may be hard on the stomach for heavy sweaters).1 Endurance athletes especially should replenish with water, sodium, and carbohydrate within the first hour after exercise to ensure the highest rates of glycogen (our stored energy) resynthesis.15 Recovery drinks with protein have been reported to maximize protein synthesis rates, consisting of approximately 0.2–0.4 g/kg/h protein and 0.8 g/kg/h of carbohydrates.16 Chocolate milk has a nice carbohydrate to protein ratio of 4:1 and is an inexpensive, but still palatable, recovery option.17

Make a Hydration Plan

In competition, every second counts. Your hydration plan should be practiced and second nature when it comes time to perform. Below summarizes some final take-home points to set you up for success in the heat. In the next and final part of our series, I will discuss cooling methods and how to identify early signs of exertional heat-related illness.

References

- Racinais S, Alonso J M, Coutts A J, Flouris A D, Girard O, González Alonso J, Hausswirth C, Jay O, Lee J K, Mitchell N, Nassis G P, Nybo L, Pluim B M, Roelands B, Sawka M N, Wingo J E, Périard J D. 2015. Consensus recommendations on training and competing in the heat. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 25 Suppl 1 : 6-19.

- González-Alonso J, Mora-Rodríguez R, Below PR, Coyle EF. Dehydration reduces cardiac output and increases systemic and cutaneous vascular resistance during exercise. J Appl Physiol 1995: 79: 1487–1496.

- Goulet ED. Effect of exercise-induced dehydration on time-trial exercise performance: a meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2011: 45: 1149–1156.

- Goulet ED. Effect of exercise-induced dehydration on endurance performance: evaluating the impact of exercise protocols on outcomes using a meta-analytic procedure. Br J Sports Med 2013: 47: 679–686

- Wall BA, Watson G, Peiffer JJ, Abbiss CR, Siegel R, Laursen PB. Current hydration guidelines are erroneous: dehydration does not impair exercise performance in the heat. Br J Sports Med 2015: 49:1077-83.

- Cheuvront SN, Kenefick RW. Dehydration: physiology, assessment, and performance effects. Compr Physiol 2014: 4: 257–285.

- Bergeron MF, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. Fluid and electrolyte losses during tennis in the heat. Clin Sports Med 1995a: 14: 23–32.

- Bergeron MF, Maresh CM, Armstrong LE, Signorile JF, Castellani JW, Kenefick RW, LaGasse KE, Riebe D. Fluid-electrolyte balance associated with tennis match play in a hot environment. Int J Sport Nutr 1995b: 5: 180–193.

- Shirreffs SM, Sawka MN, Stone M. Water and electrolyte needs for football training and match-play. J Sports Sci 2006: 24: 699–707.

- Von Duvillard SP, Braun WA, Markofski M, Beneke R, Leithauser R. Fluids and hydration in prolonged endurance performance. Nutrition 2004: 20: 651–656.

- Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, Maughan RJ, Montain SJ, Stachenfeld NS. American College of Sports Medicine position stand: exercise and fluid replacement. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007: 39: 377–390.

- Burke LM, Hawley JA, Wong SH, Jeukendrup AE. Carbohydrates for training and competition. J Sports Sci 2011: 29: S17–S27

- Lott MJ and Galloway SD. Fluid balance and sodium losses during indoor tennis match play. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 21: 492–500, 2011.

- Lopez, R. Exercise and Hydration: Individualizing Fluid Replacement Guidelines Strength & Conditioning Journal. 34(4):49-54, August 2012.

- Burke LM. Nutritional needs for exercise in the heat. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2001: 128: 735–748.

- Beelen M, Burke LM, Gibala MJ, van Loon LJ. Nutritional strategies to promote postexercise recovery. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2010: 20: 515–532.

- Pritchett K, Pritchett R. Chocolate milk: a post-exercise recovery beverage for endurance sports. Med Sport Sci 2012: 59: 127–134.

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only. Doctors cannot provide a diagnosis or individual treatment advice via e-mail or online. Please consult your physician about your specific health care concerns.

About the Author

Dr. Emily Kraus is a BridgeAthletic performance team contributor where she focuses on topics that are at the forefront of athletics and medicine. She is the incoming Stanford non-operative sports medicine fellow in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Emily has provided medical coverage for events such as the USATF National Track and Field Championships and is the research coordinator for a multi-center study focused on prevention of stress fractures in division I collegiate runners. Emily has finished six marathons, recently ran (and won) her first 50km trail ultramarathon, and placed 56th female in the 2016 Boston Marathon. Emily is passionate about injury prevention, running biomechanics, and the promotion of health and wellness.

Related Posts

Supplement Safety with Tactical...

Dietary supplements seem like the "magic pill" a tactical operator needs to perform better,...

Eating Healthy on the Go: Tips for Busy...

It's no secret that tactical professionals have weird schedules. So why do health professionals...

Post-Training Nutrition for Tactical...

Eating after a workout can be a challenge for tactical professionals. Having grab-and-go fuel...