Preventing and Managing Ankle Sprains

Soccer is currently the most popular sport played worldwide and it also, not surprisingly, happens to have the highest injury rate among high school sports, with ankle sprains occurring most frequently. Ankle sprains are a common injury in the sports world, comprising approximately 25% of all sports-related injuries.1 A prior ankle sprain is one of the greatest risk factors for a future sprain, so both prevention and optimal management of acute (new) sprains is essential. This article will briefly review the anatomy and mechanism of an ankle sprain, management options, and finally prevention strategies.

Stats on Ankle Sprains

20% of all injuries in youth soccer players16

25% of all injuries across all sports

The Anatomy

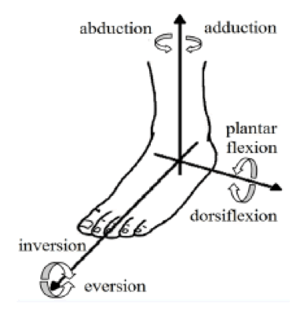

Anatomy of the foot and ankle is far from simple with the foot containing twenty-six individual bones and thirty-three joints when you add in the long bones of the lower leg.2 The ankle joint complex uses three separate joints to allow proper motion of the foot, The key motions of the ankle joint complex are dorsiflexion (pointing toes up) and plantarflexion (pointing toes down), abduction (toes out / away from midline) and adduction (toes in / towards midline), inversion (soles towards midline) or eversion (soles away from midline). These motions become important when we discuss the mechanism of ankle sprain (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Motions of the ankle

Figure 1: Motions of the ankle

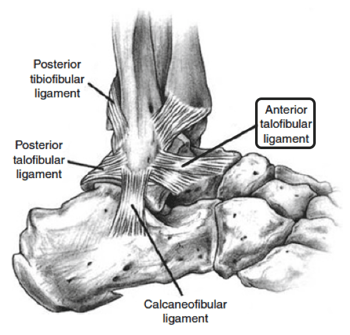

The primary lateral (outside) stabilizing ligaments of the ankle include the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), calcaneal fibular ligament (CFL), lateral talocalcaneal ligament (LTCL), shown in Figure 2. The primary medial (inside) stabilizing ligament is the deltoid ligament, which is made up of a superficial and deep layer. There are also twelve muscles within the foot and ankle which move and help stabilize the joint.

Figure 2: The lateral (outside) ligaments of the ankle. The anterior

talofibular ligament is the most commonly injured ligament.

How do Athletes Sprain Ankles?

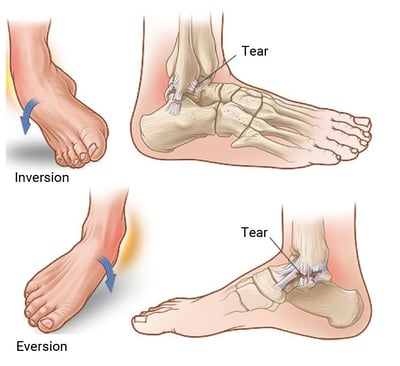

An ankle sprain is an injury to the ligaments of the ankle, which can vary in severity from stretching of the ligament to partial or complete tear of the ligament. They are usually caused by a contact injury located at the lateral aspect (outside) of the ankle. Medial (inside) and high ankle sprains (also known as syndesmotic injuries) are much less common. The ATFL is the most commonly injured ligament, caused by a sudden inversion and plantarflexion movement of the ankle (Figure 3). The second most common ligament injured is the CFL. It should also be noted soccer athletes are unique in that the risk of a medial ankle injury is slightly higher because athletes use the inside of their feet to kick and pass which puts the ankle in an abducted and externally rotated position (Figure 3). Too much movement or a trauma during this movement, can sprain the deltoid ligament.3

Figure 3: Mechanisms of ankle sprains. Inversion injuries (above)

are more common than eversion injuries (below).

In soccer, injuries often occur from direct contact with the foot or ankle, usually coming from the side as opposed to the front or back.4 Further, the ankle injury is likely to be more severe if weight-bearing (foot on the ground) than not weight-bearing (foot off ground) and more ankle sprains were seen on the dominant leg, as it’s more exposed to forced inversion.

Diagnosis and Work Up

Diagnosis always begins with a thorough history and physical exam. Usually athletes describe an inversion and plantarflexion mechanism (Figure 4) followed by some degree of swelling and bruising around the lateral (outside) of the ankle. He or she may not have been able to bear weight on the ankle after the injury. After a few days, bruising from the sprain can often extend to the toes as a result of gravity. A thorough physical exam can be difficult if the injury is very acute because the swelling can limit the ability to fully test the ligaments. Sprains are graded depending on the degree of ligament tearing and, based on clinician discretion, may warrant x-ray imaging. It should be noted that most ankle sprains do not require an x-ray.

Treatment Options

A variety of treatment options are available for the management of acute ankle sprains. Below are the most common and well-researched options.

Cryotherapy (ice) Although becoming more controversial in the rehabilitation of sports injuries, icing still plays a critical role in the acute phase of a sprain in managing swelling and inflammation during the first 3-7 days. A good system is icing for 20 min every 2 hours with the area checked periodically to avoid frostbite injury.5

Compression, support, and bracing A randomized controlled trial compared the combination of an air stirrup brace and elastic compression wrap with either method alone, and found that the combination was superior in terms of overall joint function at the 10-day and one-month follow-up.6

Mobilization: Evidence suggests early mobilization permitting the athlete to bear weight as tolerated for daily activities (functional mobilization) is superior to prolonged rest in regards to time to return to work or sports, long-term ability to return to sports, persistent swelling, and long-term ankle instability.7 Further, focused ankle range of motion exercises within the first week along with functional mobilization have been found to be beneficial for return to sport (van Rijn).

NSAIDs: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be beneficial in reducing excessive inflammation, however prolonged use can delay healing of fractured bones (if a fracture is involved) or injured tendons.8

Rehabilitation: Rehabilitation after an ankle sprain consists of specific exercises focused on proprioceptive (balance) training, strengthening, and plyometrics. In addition, a neuromuscular retraining program is highly recommended prior to return to sport (more about neuromuscular retraining below).9

Surgery: Consideration of surgical intervention is best reserved for patients with chronic ankle instability who do not respond to a thorough trial of rehabilitation.

Prevention Strategies

Although difficult to prevent a first ankle sprain, prevention of future ankle sprains is often more valuable and has been well-studied.10 Below are some excellent prevention strategies which can be applied to all sports.

Neuromuscular retraining The increased injury risk after an initial ankle sprain is generally thought to be caused by a neuromuscular impairment in the ankle owing to trauma to mechanoreceptors of the ankle ligaments and musculature.11 Examples of neuromuscular retraining exercises are described in Table 1 below.

|

Proprioception (Balance Training) Balance on one leg for 30 to 60 seconds Strengthening Range-of-motion exercises using resistance band Plyometrics Scissor hops: start in a lunge position; jump and land with the other foot forward |

Table 1:Neuromuscular Retraining Strategies5,15

Brace vs Taping: Theories differ on why external support in the form of bracing or taping prevents ankle sprains. A 2010 review looked at a number of studies and concluded that a combination of an external prophylactic measure (tape or brace) with neuromuscular retraining will achieve the best preventive outcomes with minimal burden for the athlete.12 One of the challenges with taping is it requires someone trained in taping to perform (such as an athletic trainer). Further, taping loses much of its supportive effect after as little as 30 min of play, although the proprioceptive effects are still present. Alternatively, a low profile ankle brace can be easily worn below shin guards in soccer, so this might be a better option for athletes who don’t have assistance for taping before practice and games.

Dynamic Warm-Up: There is growing evidence that a focused sport-specific warm-up (e.g., running, cutting, skips, jumps, other sport-specific movements at gradually increasing speed) before intense exercise reduces the risk of lower limb injuries.13 Here’s a dynamic warmup you can implement with your athletes.

Fair Play: According to data from the FIFA World Cup 1998–2010, foul play during competition is the cause of a large percentage of all injuries. Coaches should emphasize good sportsmanship and fair play during practice and competition.14

Summary

Ankle sprains are a common sports-related injury, and an approach to effective treatment and prevention is essential and should involve the athlete, coach, athletic trainer, rehab specialist, and physician.

-Ankle sprains are a common sports-related injury and a prior ankle sprain is the greatest risk factor for future sprain.

-The most common mechanism of injury is an inversion motion of the ankle, leading to injury to the ATFL, varying from a stretch of the ligament to partial or complete tear.

-Treatment options include ice, compression and bracing, functional mobilization, NSAID’s, and rehabilitation.

-Prevention of future sprains includes bracing or taping + neuromuscular retraining.

-A dynamic warm-up can help with injury prevention.

References

- Katcherian D. Soft-tissue injuries of the ankle. In: Lutter, LD, Mizel MS, Pfeffer GB, eds. Orthopaedic update knowledge, 1994. Foot and Ankle. Rosemont, IL: The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1994: 241–255.

- Brockett C L, Chapman G J. 2016. Biomechanics of the ankle. Orthopaedics and Trauma 30 (3): 232-238.

- Ekstrand J, Gillquist J (1983) Soccer injuries and their mechanisms: a prospective study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 15(3):267–270

- Giza E, Fuller C, Junge A, Dvorak J. 2003. Mechanisms of foot and ankle injuries in soccer. American journal of sports medicine 31 (4): 550-554.

- Tiemstra J D. 2012. Update on acute ankle sprains. American family physician 85 (12): 1170-1176.

- Beynnon BD, Renström PA, Haugh L, Uh BS, and Barker H: A prospective, randomized clinical investigation of the treatment of first-time ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med 2006; 34: pp. 1401-1412.

- Kerkhoffs GM, Rowe BH, Assendelft WJ, Kelly K, Struijs PA, and van Dijk CN: Immobilisation and functional treatment for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002.

- Mehallo CJ, Drezner JA, and Bytomski JR: Practical management: nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use in athletic injuries. Clin J Sport Med 2006; 16: pp. 170-174.

- Emery CA, and Meeuwisse WH: The effectiveness of a neuromuscular prevention strategy to reduce injuries in youth soccer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2010; 44: pp. 555-562.

- Verhagen EALM, Bay K Optimising ankle sprain prevention: a critical review and practical appraisal of the literature British Journal of Sports Medicine 2010;44:1082-1088.

- Freeman MA. Instability of the foot after injuries to the lateral ligament of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1965 ; 47 : 669 – 77 .

- Verhagen EA, van der Beek AJ, van Mechelen W. The effect of tape, braces and shoes on ankle range of motion. Sports Med 2001 ; 31 : 667 – 77.

- Fradkin AJ, Gabbe BJ, and Cameron PA: Does warming up prevent injury in sport? The evidence from randomised controlled trials? J Sci Med Sport 2006; 9: pp. 214-220.

- Dvorak J, Junge A, Derman W, Schwellnus M (2011) Injuries and illnesses of football players during the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Br J Sports Med 45:626–630

- Landon S. 12 Ways to build ankle strength for top performance. http://www.active.com/fitness/Articles/12_Ways_to_Build_Ankle_Strength_for_Top_Performance.htm. Accessed August 10, 2011.

- Kucera KL, Marshall SW, Kirkendall DT, Marchak PM, Garrett WEJr. Injury history as a risk factor for incident injury in youth soccer. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:462. Google Scholar CrossRef, Medline

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only. Doctors cannot provide a diagnosis or individual treatment advice via e-mail or online. Please consult your physician about your specific health care concerns.

About the Author

Dr. Emily Kraus is a BridgeAthletic performance team contributor where she focuses on topics that are at the forefront of athletics and medicine. She is the incoming Stanford non-operative sports medicine fellow in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Emily has provided medical coverage for events such as the USATF National Track and Field Championships and is the research coordinator for a multi-center study focused on prevention of stress fractures in division I collegiate runners. Emily has finished six marathons, recently ran (and won) her first 50km trail ultramarathon, and placed 56th female in the 2016 Boston Marathon. Emily is passionate about injury prevention, running biomechanics, and the promotion of health and wellness.

Related Posts

2022 NSCA Coaches Conference

The BridgeAthletic team attended the 2022 NSCA Coaches Conference in San Antonio, Texas January 6-8...

2021 Fusion Sport Conference

The BridgeAthletic team attended the 2021 Fusion Sport Summit - North America at the UFC...

Building Connections with Megan Young

In this episode of Powering Performance, we are joined by Megan Young, formerly the High...